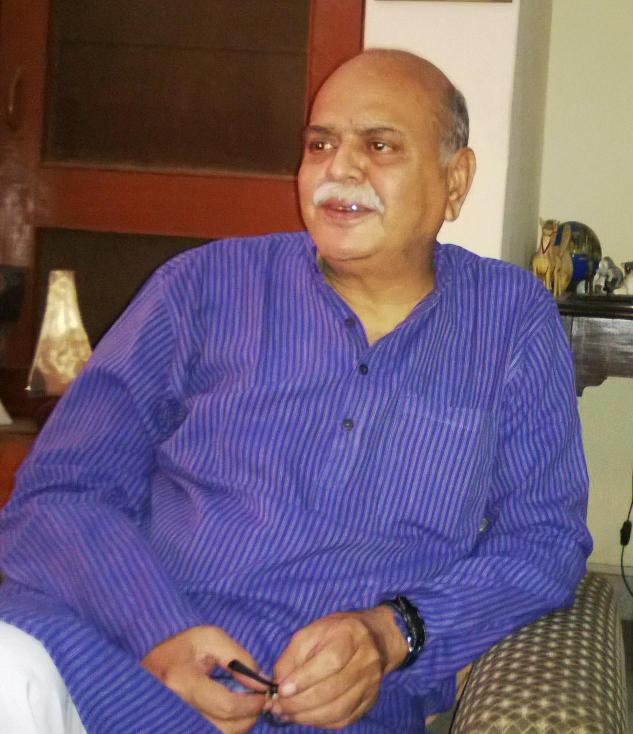

SALEEM Kidwai is a medieval historian and works in the area of culture conservation. His work includes the translation of Malika Pukhraj’s autobiography in English. In an exclusive interview with Inam Abidi Amrohvi, Kidwai shares his thoughts on Awadh and its culture.

MT: What was the Lucknow of the 50s and 60s like? Any fond memories or interesting incidents that you would like to share.

SK: I’ve memories of a slow and very civilised city. But, even then I felt there was something that Lucknow needed. Perhaps that’s why I chose to stay away from the city for 34 years.

MT: What changes do you see in the city and is there something that worries you?

SK: I found it worse. The state has become politically very active. To me Lucknow is a very provincial town, not just in being a small town but also in attitudes. One one level I find the people extremely tolerant and kind and on the other not open to new ideas and change.

On the positive side, infrastructure facilities have changed drastically. It remains a wonderful city to retire in. But, I don’t want to be young in the city.

MT: Do you feel the tolerance level of the Nawabs was partly responsible for the strong roles tawaifs played during that period? Also how did the kothas doubled up as centres of tehzeeb.

SK: It was not just the tolerance of the Nawabs, but the tolerance of the Awadh of that era, towards clothes, fashion, dance, food, etc. They were very experimental and indulgent, and had lot of money. So it was but natural that the tawaif culture would flourish.

Coming to the second part of your question, the tawaifs were the only public women of the society of the time. These public women couldn’t have been vulgar, they had to match the sophistication of the rest of the culture. It was actually the business of them learning tehzeeb to deal effectively in public space. If you look, most poets were connected with them, everyone wanted their ghazals to be sung by them, and the best musicians were employed to teach them. To me, they were actually among the shapers of society.

MT: Qawwalis, with their Sufi touch, have been popular despite not much change in the rendition. What do you owe this to?

SK: Any music cut across boundaries. Qawwalis in general are very organic, they were never a fashion craze. If you look at the sources of qawwali they are very many. Just like Indian Sufism has fed upon many local influences, qawwali too, was sung in all sorts of local dialects. It used very basic beats and works mainly on continuous rhythm.

More importantly, qawwali was never a court art. It was always a people’s art. So, it was natural for it to become popular.

MT: You said some time back that you ‘acquired’ Urdu because of Begum Akhtar. Do you feel Urdu is losing out today because of a lack of both, good quality Urdu poetry and singers well versed with the language?

SK: Urdu was affected both by the politics of the nation and the partition. I think where we’ve lacked behind, both in Urdu and this whole idea of the cultural legacy of Awadh, is that we have made or continue to make Urdu a Muslim language. In the same way that we continue to associate somehow the Awadh legacy with Muslims.

MT: What was the most difficult aspect of translating Malika Pukhraj’s autobiography? Is there any other similar project that you are working on or would like to pursue?

SK: It was mostly an exciting work, though badly handwritten. More than half of it was one sentence, forget the paragraph.

The Lahori Urdu used was also not the language I spoke. For somebody coming from Lucknow that came across as impolite. So that aspect was to be changed in the translation. And that was a challenge.

I’ve just finished translating the work of a Lucknow-born author, Syed Rafiq Hussain, known perhaps only to old academicians of the city. He died in 1944. The book is a collection of some of the most amazing short stories about animals and humans, originally published as Aina-e-Hairat. For me cultural conservation is this, find someone completely forgotten and reestablish him, so the people know him.

very nice interview