IT WAS 1935. The union hall of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) was brimming with excitement. A young man in sherwani stands up to recite a poem ‘Inquilab,’ in his inimitable style –

“KohsaaroN ki taraf se surkh aandhi aayegi

Ja-baja aabaadiyoN meiN aag si lag jaayegi

Aur is rang-e-shafaq meiN ba-hazaraaN aab-o taab

Jagmagaaega watan ki hurriyat ka aaftaab”

[A red storm is approaching from over the mountains

Sparking a fire in the settlements

And on this horizon, amidst a thousand tumults

Shall shine the sun of our land’s freedom]1

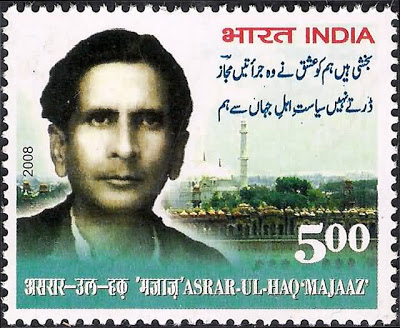

The hall reverberates with a thunderous applause. Asrar-ul-Haq Majaz by now was already making waves in the literary circles.

The poetic journey

Majaz’s poetry first made its mark in the culturally alive AMU during the early 1930s. His poems ‘Noora’ and ‘Nazr-e-Aligarh’ established him as a popular poet. The girls loved him.

“NahiN jaanti hai, mera naam tak woh

Magar bhej deti hai paighaam tak woh

Ye paighaam aate hee rahte haiN aksar

Ki kis roz aaoge beemaar hokar”

[She doesn’t even know my name,

But still she sends me messages!

These messages come often

“When will you fall sick, come here again!]8

Majaz’s popularity overshadowed all his contemporaries at AMU, including poets such as Ali Sardar Jafri, Jaan Nisar Akhtar and Jazbi. He finished his graduation at AMU in 1936. The same year Professor Ahmed Shah Bukhari, popularly known as ‘Pitras’ Bukhari, calls Majaz to Delhi. Bukhari made him join the newly formed All India Radio as editor of a journal. Majaz named it ‘Awaaz’ and managed it for a while. Their relationship soured for some reasons and Majaz left the station.

This was also the time when the door of the married woman Majaz loved, closed on him. It left a permanent scar on his psyche. He became a compulsive drinker. Majaz’s personal grief merged with his rebel ideas. The result was ‘Awara’ – a masterpiece of the era.

“Shahar ki raat aur maiN naashaad-o-nakaara phiruuN

Jagmagaati jaagti saDkon pe awara phiruuN

Ghair ki basti hai kab tak dar badar maara phiruuN

Aye gham-e-dil kya karoon aye wehshat-e-dil kya karuuN”

[The night in the city and hopeless and idle I roam,

On the twinkling, moving roads idle I roam,

In this town of strangers how long shall I homelessly roam,

Oh! Sad heart what shall I do, Oh! Troubled heart what shall I do!]8

The poem became an anthem for the revolutionary youth of the time. The word Awara suddenly meant more than just troubled and jobless-

“Le ke ek changez ke haathon se khanjar toD dooN

Taaj par us ke damakta hai jo patthar toD dooN

Koi tode ya na toDe maiN hee baDhkar toD dooN

Ai gham-e-dil kya karoon aye wehshat-e-dil kya karooN”

[I shall snatch the dagger from the hand of Changez and break it,

I shall break that gem that glitters in his crown,

Whether any one dares or not I alone shall break it,

Oh! Sad heart what shall I do, Oh! Troubled heart what shall I do!]8

Heartbroken, Majaz came back to Lucknow.

A nationalist to the core, Majaz along with his friends Ali Sardar Jafri and Sibtey Hasan, took out the progressive journal ‘Naya Adab’ from Lucknow. It was established with funds from the CPI in 1939 under the auspices of UPWA (Urdu Progressive Writers’ Association). The journal was the most influential progressive literary monthly of the period, so much that its first three issues actually laid the theoretical foundations of the UPWA movement.2

Naya Adab ran for a decade. After its closure, Majaz joined the Harding Library at Delhi as Assistant Librarian. There he collaborated with Fasihuddin Ahmed in editing the literary journal ‘Adeeb’.3

Knowing the man

Majaz was a fragile soul. Being the nice guy he was, Majaz kept quiet even when friends misbehaved with him.

“Awara-va-majnu.N hee pe mauquf nahiN kuchh

Milne haiN abhi mujh ko Khitaab aur zyadaa”

[They have not stopped at vagabond and rogue

More titles are to be bestowed on me]

Majaz had a great sense of humour. Once somebody’s poetry didn’t go down well with him. He had this to say – “Don’t worry, when your poems are translated into Urdu then people would recognise your talent.”4

He was also a rebel poet. Majaz’s anger against the capitalist system provided the basis for Awara. His hope for a better tomorrow, born out of the socialist ideology of the Soviet Russia, is expressed in the poem ‘Khwab-e-Sehar’-

“Yeh musalsal aafaten, yeh yorishen, yeh qatal-e-aam

Aadmi kab tak rahe ohaam-e-baatil ka ghulaam

Zehn-e-insaani ne ab ohaam kee zulmaat meiN

Zindagi ki sakht toofani andheri raat meiN

Kuch nahin tau kam se kam khawab-e-sehar dekha to hai

Jis taraf dekha na tha ab tak udhar dekha to hai”

[Such struggle, such suffering, such heinous carnage

How long has man been to superstition a slave

Human mind has at last awakened from its heavy sleep

In the stormy night of life, in the superstitious deep

Has at last dreamt a dream of the golden dawn

Looked at last towards the East, where none before had glanced]5

The woman in Majaz’s poetry was more than an object of beauty. He wished to see them as crusaders who could revolt against exploitation and injustice.

“Teri neechi nazar khud teri ismat ki muhafiz hai

Tu is nashtar ki tezi aazma leti to achha tha

Teri maathe pe ye aanchal bahut hi khoob hai lekin

Tu is aaNchal se ik parcham bana leti to achha tha”

[Your lowered gaze is itself a protector of your purity,

If you now raise your eyes and test the sharpness of it, it would be good;

The cloth covering your head is no doubt a good thing,

But if you make a flag out of it, it would be good]6

Majaz was also faint of heart. In the 1946 sectarian riots, he witnessed a killing in Bombay and could not eat for three days. He ran out of a science class on seeing a frog in the lab. It did not stop there and he actually left science altogether.

His drinking and poetry gave vent to his heartbreak. Once Jigar Moradabadi asked him to quit drinking, to which Majaz replied – “You left it just once, I left it several times.”4

Josh Malihabadi once said about Majaz, “He wants to capture the entire beauty of the world in a single glance and to drink all wine of the world in one gulp.”4

“Is mahfil-e-kaif-o-masti me, is anjuman-e-irfaani me

Sab jaam-bakaf baithe hi rahe, hum pee bhi gaye chahlka bhi gaye”

[This gathering of fun and frolic, the erudite all around

All merely sat with goblets while I drank to the full]

But who could know the man more than he himself! Majaz the poet summarises the man in his poem ‘Ta’arruf ‘ –

“Khoob pehchaan lo, asraar huuN maiN

Jins-e-ulfat kaa talabgaar huuN maiN

Ishq hee ishq hai, duniya meri

Fitna-e-aql se bezaar huuN maiN”

[Look at me, recognise me well, for I am Asrar

I seek love and longing

My world comprises love and just love

I know not the devil of the intellect]7

Path to self-destruction

By the early 1950s, Majaz’s mental faculties started deteriorating. His drinking further compounded his misery. His genius still helped him to pen poems like, ‘Khawab-e-Sehar’, ‘Shaher Nigaar’, and ‘Andheri Raat ka Musafir,’ which reflects on his last-ditch attempt to turnaround his messed up life.

His poem ‘Aitraaf’ was his swan song. Majaz lost hope and accepted defeat-

“Wo gudaaz-e-dil-e-marhoom kahaaN se laooN

Ab maiN wo jazba-e-maasoom kahaaN se laooN”

[That tender heart, long dead, beats no more

That innocent passion, long gone, excites no more]

In 1952, Majaz accompanied doctor Saifuddin Kichlu to attend the All India Cultural Conference at Calcutta. He was just a shadow of his old self. Sardar Jafri gave him five Rupees every evening for a drink during Majaz’s stay there. The rest of his drinking sessions were sponsored by visitors at the bar. One day he asked for ten Rupees. When Jafri tried to reason with him he said, “Sardar you’ve a family, a house, and you do poetry. What do I’ve? Now you don’t even allow me to drink!”4

Majaz landed in Ranchi’s mental asylum the same year. The poet who never wrote a weak couplet now struggled with words. This verse recovered from his belongings tells a lot about his mental state – “Woh regzaar-e-khayal me hai kabhi kabhi humkharaam meri.” [That wasteland of thoughts is walking alongside me]7

The end

Jafri recalls seeing Majaz last in the December of 1955 when he arrived in Lucknow from Bombay, to attend a Student Cultural Conference. Majaz met him at Hazratganj and showered the same love and affection on his old buddy-

“Humdum yahi hai, rahguzar-e-yaar-e-khushkhiraam

Guzre haiN laakh baar isi kahkashaN se hum” *

[This slow pace, this path of bliss has been my companion

I have passed this galaxy a million times]

They went to the conference at Baradari in Qaisarbagh together. Majaz the poet, and person, seems to come alive that night during the mushaira. He recited the following couplet several times to an eager and appreciative audience-

“Bahut mushkil hai duniya ka savarna, teri zulfoN ka pech-o-kham nahi hai

Ba-ise-sayle-ghamo-sayle-hawadis, mera sir hai ki ab bhi kham nahi hai”

[I wonder if my life gets sorted out, the way your entangled locks do

A sea of sadness surrounds me, I’m standing tall somehow]

The next day it was 4th of December. Majaz stayed with Jafri and Sahir Ludhyanvi at the hotel. Sahir bought a bottle of fine wine for Majaz. He was made to promise not to drink during the day and to not go out with his friends. They even locked the bottle inside an almirah on Majaz’s own suggestion. As if he had a premonition of things to come, Majaz told Jafri twice to spend more time with him as he seems not so sure of the future.

Jafri and Sahir reached the hotel late as they had to attend a tea party after the conference. Majaz left during their absence. They searched for him in vain. He didn’t turn up for the conference on the 5th of December. At five in the evening, the fears proved real. Somebody informed about Majaz lying motionless at the Balrampur Hospital. The conference was postponed. Everybody rushed to the hospital. The poet had an oxygen mask on him and the doctors showed little hope.

It was a result of the previous night of revelling. Majaz’s friends took him to a tavern in Lalbagh where they all drank on the rooftop. One by one they all left leaving Majaz alone in the cold winter night. The next morning he was rushed to the hospital where doctors diagnosed a brain haemorrhage and pneumonia.

A female fan sharing the name of his beloved sat next to him when Majaz passed away that night. At the age of 44, the poet was at peace finally.

Majaz often reached home late or not at all. Aware of this habit, his mother put his food, a packet of cigarettes, and fifty paise, next to his bed. The rickshaw-pullers of the city, who knew Majaz well, dropped him home and took the fifty paisa coin. That night everything changed. Majaz’s mother was waiting on the floor next to his bed. Her son was coming home for good this time.

“Ab iske baad subah hai aur subah-e-nau majaz

Hum par khatm shaam-e-ghareeban-e-Lucknow”

[Tomorrow awaits a new dawn ‘Majaz’

For with me ends the darkness of Lucknow]

Like a shooting star, Majaz, in his self-destruction left behind a trail of brilliant compositions that forever illuminate the firmament of Urdu poetry. Every time the students and alumni of AMU, like me, sing the university song, at their campus and elsewhere in the world, Majaz comes to life.

“Ye meraa chaman hai meraa chaman, maiN apne chaman kaa bulbul huuN

Sarshaar-e-nigaah-e-nargis huuN, paa-bastaa-e-gesuu-sumbul huuN”

[Narcissus’ glances have made me joyous, Hyacinth’s tresses have bound my feet,

This is my grove and my grove and I’m its nightangle]8

And so the great poet lives on, the way he always did – as the cynosure of all eyes!

* Ali Sardar Jafri used this couplet as the title song of his famous television series, Kahkashan, broadcasted on Doordarshan during the early 90s.

(Based on Ali Sardar Jafri’s account in ‘Lucknow ki Paanch Raatein’.)

NOTES

1 Kuldip Sahil, A Treasury of Urdu Poetry From Mir to Faiz: Ghazals with English Renderings (Delhi: Rajpal & Sons, 2009), 114-119.

2 Geeta Patel, Lyrical Movements, Historical Hauntings: On Gender, Colonialism, and Desire in Miraji’s Urdu Poetry (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001), 111.

3 Abida Samiuddin, Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Urdu Literature (New Delhi: Global Vision Publishing House, 2007), 387.

4 Ali Sardar Jafri, Lucknow ki Paanch Raatein (New Delhi: Rajkamal Prakashan, 2010), 25-58.

5 K. C. Kanda, Masterpieces of Patriotic Urdu poetry (Delhi: Sterlings Publishers Private Limited, 2009), 323-339.

6 “Ghazal as a form of Urdu poetry in the Asian subcontinent”, accessed December 5, 2011, http://www.ghazalpage.net/prose/notes/ghazal_urdu.html.

7 Rakhshanda Jalil, email message to the author, December 8, 2011.

8 Dr Sami Rafiq, Aahung: Poems by Asrarul Haq Majaz Translated into English (New Delhi: AuthorsPress, 2014), 88,111,91.