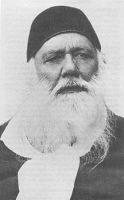

THE name Sir Syed Ahmad Khan evokes considerable respect from people in India, especially Muslims on either side of the border. A man of vision, he thought of progressive Muslim education on a scale rarely attempted earlier and against formidable odds. It is important to understand what drove him to bring in modern education as a savior of Muslims.

THE name Sir Syed Ahmad Khan evokes considerable respect from people in India, especially Muslims on either side of the border. A man of vision, he thought of progressive Muslim education on a scale rarely attempted earlier and against formidable odds. It is important to understand what drove him to bring in modern education as a savior of Muslims.

The Prophet of Islam [PBUH] said, “There are two persons that one is permitted to envy: The one to whom God has given riches and who has the courage to spend it in search for truth; the other to whom God has given knowledge and wisdom and who applies it for the benefit of mankind and shares it with his fellows.” Sir Syed belong to the second group.

The latter part of the 19th Century saw the decline of Muslim dominance. Spain had been lost, the Middle East was in chaos, and West Africa was about to be conquered by Spaniards and French. The mighty Ottoman Empire was crumbling. The Indian Muslims had lost their seat of power. (1) It was under such difficult times that Sir Syed raised the banner of education for Muslims, one that promises to halter the declining fortunes of the community. He thought of education as a perfect tool for social change, rather than romanticising over a glorious past. This was something which life taught him a bit early.

Sir Syed was born on October 17, 1817, at Delhi. His father Muhammad Muttaqi, paternal gradfather Syed Hadi, and maternal grandfather Khwaja Fariduddin, all held prominent positions in the Mughal Court. (2) Sir Syed was taught the Quran by his mother Azis-un-Nisa, something unconventional at the time. It was during these formative years that the importance of education reached him. He learned Persian, Arabic, Urdu, Islamic studies, astronomy, and mathematics under different tutors. Not to be left behind in other areas, Syed was actively involved in Mughal court’s cultural activities.

This was also the time when Sir Syed’s elder brother Syed Muhammad Khan established city’s first printing press in Urdu together with the journal Sayyad-ul-Akbar. (2) After his father’s death, financial difficulties forced him to discontinue his formal education. Sir Syed took up the charge of his late brother’s journal after refusing offers from the Mughal court. Later he was to work for the British East India Company. He knew very well where the future lay.

While working for the British Sir Syed wrote several books, including a commentary on the Bible (Tabyin-ul-Kalam) – the first by a Muslim. (2) The scholar in him stood out during this period.

The revolt of 1857, also known as the first war of independence, was a turning point in Sir Syed’s life. He was prudent enough to realise that such ill organised attempts to dislodge the mighty British empire in India were not enough. But what followed made him politically more active for the rest of his life.

Muslims bore the brunt of the brutal crackdown that followed, and the gulf widened between them and Christians. Driven by the events, Sir Syed came out with his most famous literary work, ‘Asbab-e-Baghawat-e-Hind’ (The causes of the Indian revolt). It was mainly to dispel the theory of the revolt being mainly a Muslim conspiracy. He argued that the British failed to recognise rights of the natives in their own land. But he also blamed his own community, admonishing them for giving patronage to religious orthodoxy and a failure to keep up with modern times. Syed was of the view that nothing in Islamic belief and practice could oppose reason. He even wrote an unfinished commentary of Quran to further his point.

In spite of the great divide that resulted between Muslims and Christians, Sir Syed tried hard to bring the two communities together by highlighting areas of shared interest. He thought that Islam and Christianity can coexist, and opposed the idea that English practices were bad.(4) Syed was well aware of the changing times and how progress was eluding the Muslim community because of its isolation.

Realising the urgent need of modern scientific education as an enabler of social and economic growth of Indian Muslims, Sir Syed established a number of madrasas, and journals, including Tahzeeb al-Akhlaq (the social reformer) that promoted his idea. The first such school he opened was at Moradabad in 1858, to teach modern history. He thought it would help Muslims to learn about other civilisations and societies, and how they failed when they did not keep up with changing times. Syed’s idea was to change a complete mindset through self-analysis and criticism before bringing in any solution. ‘The Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College’ he established in 1875, against tremendous opposition from the clergy, was the culmination of a remarkable journey to seek a new model of education for Muslims.

Perhaps inspired by the memory of his mother, Sir Syed chose Sultan Shah Jahan Begum as the first chancellor of the university.

With an eye on Muslim representation in the government and civil services Sir Syed supported the efforts of Surendranath Banerjee and Dadabhai Naoroji in this area. (2) He even established the Muhammadan Civil Services Fund Association in 1883, to encourage and help aspiring Muslim graduates.

Sir Syed was knighted by the British government in 1888. He died a year later on March 27th. In a way he was lucky that he saw in his lifetime the seeds of ‘change’ bearing fruits of ‘success’. The recognition too followed.

It’s not mere coincidence that the global Muslim community today is once again struggling with the same old issues. Turmoil in the Arab world, paranoia about Islam and Muslims in the West, and a surge in Muslim extremism, are the same obstacles that Sir Syed Ahmad Khan started with. That makes the methods he adopted to counter such problems all the more relevant today. Education, reconciliation, peace, and progress, are once again the need of times.

The first verse of Quran revealed to the Prophet Muhammad [PBUH] was ‘Iqra’ (Arabic for ‘read’). The holy book itself stresses the importance of education. Sir Syed took the lead from the Quran and worked tirelessly to bring Muslims into mainstream. He believed and rightly so that ‘the purpose of education has always been to distinguish between right and wrong, and to live a dignified and disciplined life.’ (1)

As we celebrate another anniversary of this great reformer, it’s time to spend a few thoughts on the great cause to which Sir Syed dedicated his life. We need to understand and appreciate his model of Muslim empowerment. The original ‘Aligarh Movement’ was based on the principle of change from within and a tolerant worldly outlook. It aimed at equipping Muslims with modern education, something which even the religion permits. This is the legacy that Sir Syed Ahmad Khan left behind and which holds true to this day.

If one university in Aligarh can bring about so much change, 100 others across the globe could do much more!

NOTES

1 B.R. Sinha, Education and Development, Volume II, Country Studies in Educational Development (New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, 2003).

2 Nikhat Ekbal, Great Muslims of Undivided India (Delhi: Kalpaz Publications, 2009).

3 N. Hanif, Islam and Modernity (New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, 1997).

4 Shan Muhammad, Education and Politics: From Sir Syed to the Present Day : (the Aligarh School) (New Delhi: APH Publishing, 2002).